PSU Neuropsychology of MS Program

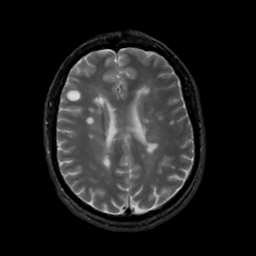

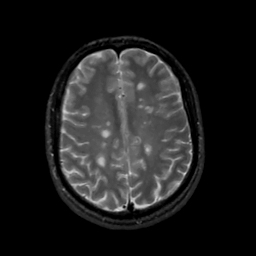

In the field of neuropsychology, we attempt to understand higher level cognitive processes (like attention, memory, speeded information processing, etc.) in the brain, particularly in individuals with neurological diseases. One area we have focused on in my lab is studying persons with multiple sclerosis (PwMS). MS is a disorder of the central nervous system that results in the destruction of the white matter (in particular, the myelin) in the brain. This destruction is thought to occur through some autoimmune process but the mechanism underlying that process is currently not well understood. MS typically strikes people in their 20's and 30's, just as they are starting their careers/families, and PwMS typically live many years with their symptoms, so it is a particularly devastating disease. It affects women more than men by about a 3:1 ratio, is more common in geographical regions farther away from the equator, and tends to differentially affect individuals of Western/Northern European ancestry.

A thread that has organized the research program in my lab involves the study of secondary factors that may influence cognitive performance in PwMS. On the surface, it may seem relatively simple to administer a neuropsychological test to measure a particular cognitive function (e.g., memory, information processing speed), see how PwMS perform relative to normative data or controls, and draw conclusions about their cognitive profile based upon their relative performance. In actual practice, interpreting neuropsychological tests, especially in individuals with neurological disorders (like PwMS), is extremely challenging.

One reason for this is that multiple non-cognitive factors can interfere with performance on these tests. For example, depression is common in many neurological disorders, and has been shown to interfere with performance on many types of effortful cognitive tasks. Thus, an individual with a neurological disorder could perform poorly on a demanding set of cognitive tasks not because of any primary cognitive difficulty emanating from the neurological condition, but because of the secondary effects of depression.

Another important thread of the research program in my lab at Penn State has focused on developing a better understanding contributors to depression in MS.

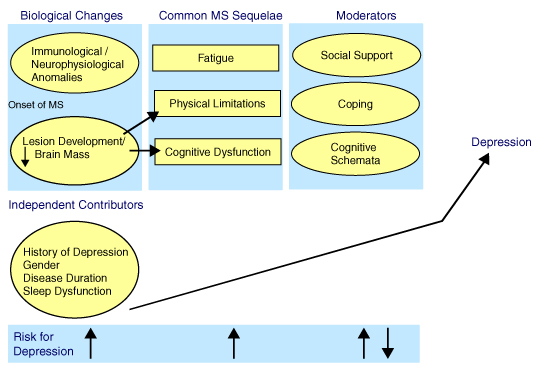

Model of Depression in MS

A model of depression guiding but also formulated by our research is illustrated and described in the model above. Prior to the onset of MS, there is no elevated risk for depression among individuals who ultimately develop the disease. Subsequent to developing MS, there is an elevated risk for depression. We have developed this model to attempt to explain in an integrated fashion what might account for that elevated risk, because it must have something to do with having MS. All of the factors included have some empirical support in being associated with depression. That is, there is at least one study, and in most cases several studies, that have shown that these variables are associated with depression. Factors that are circled have been shown by at least one study to be significantly and independently associated with depression in MS. The proposed moderator variables are theorized to moderate the relationship between the common MS sequelae and depression, but also have been shown to be directly associated with depression in MS.

The Biological Changes variables have been shown to be associated with both physical/neurological changes and cognitive dysfunction in MS, in addition to being directly associated with depression. At the bottom of the figure is a “Risk for Depression” line. Arrows depict whether the variables in that column increase or decrease the risk for depression. In the case of moderators, note that there are both up and down arrows. This is to denote that, in the case of each variable, risk is either increased or decreased depending on the nature of the variable identified. In the case of social support, good social support has been shown to be associated with reduced depression whereas poor social support is associated with increased depression in MS. For coping, higher levels of problem-focused/active coping and lower levels of emotion-focused/avoidance coping have been shown to be associated with reduced depression whereas the inverse of these has been shown to be associated with increased depression.

For “Cognitive Schemata,” positive schemata are theorized to provide a buffer against depression whereas negative schemata increase the risk for depression. In the case of the “Common MS Sequelae,” the available literature is mixed in that some studies show positive associations with depression and others no association.

The “Independent Contributors” could conceivably fit more directly into the model, but at this stage, they are simply noted to be directly associated with depression because the research literature supports such a direct association. The presence of these independent contributors further increases risk for depression when patients have a history of depression, are female, are early on in the disease process, and have problems with sleep.

It is not intended for the model to be entirely linear and unidirectional. It is assumed that depression feeds back on the moderator variables, and possibly to other variables as well including fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep problems.

Besides our work in multiple sclerosis, we also have a Neuropsychology of Sports-Related Concussion Program.